The Greece-China Connection

The Origins of the Olympic Games |

|

HELLAS, “the special oil,” and ATHENS,“the charming”To engage in an issue that contradicts what is formally accepted, and on which there are no written sources, requires courage, imagination, and intuition. You’re in a closed room in utter darkness, groping towards a window, in order to somehow illuminate the space. If at one time Greek and Chinese were indeed one language, this presumes a shared life by these peoples, and a common cradle for mankind in general, in Asia rather than Africa. Those who then left from there through a river passing [in present-day Nepal] would have brought their language as well as their mythology and traditions, religion and art with them. On their journey, which took thousands of years, they would have nostalgically given familiar names to mountains and rivers they traversed, and to the new settlements they established. Apart from Thebes in Egypt, we have a Thebes in Boeotia (north of Athens, in Greece); we have a Malta in the Mediterranean, but also in Siberia, and in Messinia; Erasino river in Argolis (Peloponnesus), Kalavrita, Eretria (Euboea), and in Vravron (Attica). The Ladon river is in Elis, and also in Kalavrita; Kifissos is in Phocis, and also in Attica; there is a Naousa in Paros, and one in Beroia. And the mountains Parnassus, Parnes, and Parnon all have names with similar meanings. The highest mountain in Greece, Olympus, the mountain of the gods, has namesakesin and outside of Greece: in Lauretiki (Attica), Bythinia, Laconia, and on the islands of Euboea, Karpathos, and Lesbos; and abroad in Cyprus, and Asia Minor (in Mysia, Ionia, and Lykia). We can assume that mountains with the same name existed in Asia. A parallel example supports this view: the Turkish name Balcania, the medieval name of the Haemos (AIMOS) peninsula, originates from Bulcan (the u is pronounced uh, as in the English word “but”), which is the sacred mountain of Mongolia (today the name of a city and province in Northern Mongolia). This was the starting point of Genghis Khan, (1167 - 1227) who expanded his empire from China to the Danube river and Eastern Europe. China also had sacred mountains, one in each large province that comprised the empire (at each of the four cardinal points, and one in the center). It is likely that one of these Chinese mountains had the now-forgotten name Olympus; that is, one of these mountains was probably renamed, whereas Greece’s Olympus has retained its name to the present. It is known that every year the Chinese Emperor would visit one of his provinces, and that each time (see The Other Santorini, p. 36) his reception was organized with musicians, theater, and gymnastic and nautical games in his honor. (Because China had 50,000 rivers and thousands of lakes, the holding of contemporary sailing races was not difficult: the Chinese were familiar with sailing contests.) This would provide a viable explanation for the establishment of these Olympic events every four years, and would establish the origins of the Olympics in China.

Such a theory is possible for

consideration, otherwise we are in danger of being

considered overindulgent, foolish, and even

ethnically

chauvinist.

The word unfortunately does not exist in

science, but do we have the right to tear down

illusions and deprive a culture of its age-old

primacy, even if it is not true, even if it is a

false one?

In Greek the meaning of the word Olympus is

not obvious, but it can be explained in Chinese.

Today the Chinese call Olympus Aolinpi:

ao is an ancient Chinese word for “south,”

while lin means

“forest”

and probably “mountain,” as mountains were covered

with

trees.

The word has nothing to do with the notion of

height, since the name also refers to the

flat areas as well as Olympia where the games

originated.

(This area was probably chosen for the games since

it also had [what was then] the only navigable

river in Greece, Alpheios, which was used for the

nautical

races.)

In addition Altis, Olympia’s sacred grove,

may also have a linguistic relationship to the

gold-mining mountains Altai in Mongolia

(despite the difference in pronunciation

designated by the different breathing

marks),

since it was on the banks of the Alpheios, which

contained fragments of gold in its

riverbeds. The Altai or Altaika mountains in central Asia had layers of gold, silver, and copper at a height of 1,500 m and their highest peaks in Mongolia measure 4,373 m. Furthermore the word ekecheiria, “sacred truce,” is the same in Chinese. In fact, although we cannot translate it directly into Greek, the Chinese qiu (*kiu) he means “I beg peace.” The tripod, trophy of the Olympic games, in China was awarded to champions and theater actors (see The Other Santorini, p. 339). Theater productions were presented by itinerant companies on hillside terraces (particularly where tea was cultivated), something which inspired the stepped seating of amphitheaters (see The Other Santorini, p. 35). To my surprise, in the 1998 Ministry of the Aegean publication on the island of Sifnos, I read that a French traveler (P. Jourdain) had also, in 1825, compared the cultivated terraces of Sifnos to the seating of a theater. The successive rings, the symbol of the Olympics, was known in China (see Agamemnon’s Mask and Panchen Lama, p. 181), and even today decorates the balconies of traditional towns there. The rings symbolize a snake, the warder of evil, and gratings on the balconies generally have symbolic representations of snakes (zig-zags, meandering lines, braids, etc.), to obstruct evil from entering a building. On an 11th century temple in India we have a high-relief representation of the God Siva crowning a king with a snake (seeThe Civilization of the Snake, p. 99) becauseit seems winners of the games and heroes were crowned with snakes, and decorated their necks, arms, wrists, waists, thighs, and ankles with snakes. On a black-figured vase in Munich a judge is crowning a young Olympiad champion with a red ribbon, which symbolizes the snake; similar ribbons appear on his arm and thigh (see The Civilization of the Snake, p. 135); a statue of an Aphrodite of the Hellenistic period also has snakes in relief on the arm, ankle, and left thigh. Recently in celebrations of the Union with China in Macao, during the Dragon dance in the Festival of Spring, the dancers wore red ribbons around their foreheads and arms. If customs were the same during the Olympic games, for example holding the games during a full moon, with similar contests and trophies, then perhaps the location where the games took place also had the same name. Mongolia is considered a “mountainous country,” far from any oceans. The fact that the Chinese always refer to the sun as “setting behind the mountains” even when it is setting over water, causes us to wonder where the origins of man were. Could it be Mongolia , rather than Africa ? It was from there that the still uncivilized hordes of barbarians descended, so that in Chinese the North came to signify a place behind “the back and spine,” “cold,” and “Evil,” and it became the place where they buried their dead (as did Jews, Greeks, and Muslims). Whereas they considered the South to be the blessed direction, where they would face the main entrances of their houses as well as their palaces (the Forbidden City of Peking, Minoan, and Mycenaean palaces).

The Mongolian love of the sea was so great that

they named their king

Genghis,

the Turkish word for “ocean,” which meant “wise

and deep

wisdom.”

The word in Tibetan is

tale

(thala-ssa,

qalassa

=

“sea” in Greek; the

q

often

takes the place of

d

), which rendered in English is

dalai.

(

Dalai lama

in

Tibet

means “man of deep wisdom, ocean of

wisdom.”) Genghis Kahn set forth from Bulcan, the sacred mountain in Mongolia , and this is the name the Turks gave to the Aimos mountain range (Balcan), which confirms their origins. The Chinese are the only people who call Greece by the same name as Greeks do: Hellas; in Chinese: Xilla-Silla; whereas all others, including the Japanese, call it Greece. Silla is also an area and kingdom of the 1st century B.C. in South Korea ; and Sila , with one l, is a plain in southern Italy (Calabria ) with fir as well as olive trees, where there are still Greek-speaking villages I had been inquiring about the meaning of the word Silla in Chinese, anxiously and with no result, until a University professor from Singapore visiting the Acropolis in 1988 told me I was fortunate to have found her to ask; and that in fact the word xila means ‘special oil.’ I always regret that I wasn’t bold enough to request her name and address. The characters of the ideograms are indeed similar, and the first, xi , meaning “rare, special” is in use today with that meaning when used in combination with other words ( xi han = “rare”); while the second, la , again in syllable combination, today means “fat” ( la zhu = “candle made from fat”). In the word Xilla , the right portion of the syllable xi remains the same today; while the left one has been added; and of the syllable la , again only the right portion remains the same (the left has been added.) In addition, although the word Xilla (*Hilla) is made of two syllable-words with different meanings, the name Yadian , “ Athens ,” is made of two syllable-words with the same meaning, where the second syllable emphasizes the first. In Chinese it is common for a one syllable-word to be repeated, for emphasis; for example xie xie, “thank you.” Also, when two different syllables with the same meaning are used in conjunction, a strict sequence of priority applies. Of course there are exceptions, for example it is always gou mai “I buy” (not mai gou ) but in the instance of the words AthinaYadian, both syllable-words mean “attractive,” “wonderful,” “charming,” and can be reversed: Dian ya) . The y which later was no longer pronounced, in Alexandrian times was replaced by the soft breath mark; and d (d), as is frequently the case, was replaced by q (Yadian - Aqhna) . Today the Chinese call Athens Yadian , “the joyous,” “the charming,” whereas for the beloved daughter of Zeus Athena they add the suffix na (Yadian na) .

And here we should wonder: Were the names

Hellas

,

and

Athens

given by indigenous people – people born in

Greece

? Or

by others who came from far away, from the

North?

How were places

named?

Was the christening simultaneous with first

impressions and analogous memories when a place

was first

settled?

Or later, according to learned characteristics of

the land

itself?

The Oracle of Delphi gave useful directions for

where the founding of new towns or settlements

should take place. Once, the oracle advised

a people to build their colony opposite the city

of the "blind,"meaning that the site of Byzantium

(present-day Istanbul) on the European side was

most privileged and exquisite, but the earlier

settlers did not realize that, and built their

town on the opposite coast of Asia minor (known

today as Scoutari). “The first people of Hellas ,” Socrates once said to Kratylos, without it being clear if he was referring to the indigenous people, or to foreigners – the first people who came to Hellas . Does the Yunnan province of southern China bear any relation to the Ionians ? (Two n `s instead of one do not pose a problem.) Is this why Arabs and Turks refer to Greeks as Yunan ?

At this point it should be emphasized once again

that we must release ourselves from “the bind of

same-sounding words” (that are not related), and

not hesitate to link words together that sound

similar, when they also have similar

meanings.

A similarity in sound is not enough to prove the

relationship of two words, but when the meaning

also coincides, then of course the words

are

related.

In other words, we should not be afraid, for

example, to link the Soraksan range in Korea to

the Sarakatsanaioi, Greek nomads in

Thessaly and Macedonia who had probably originally

come from South Korea and followed the same route

as Genghis Khan to the Balcans. |

|

|

The olive tree, one of the ancient trees from before the Flood, is the most characteristic feature of southern Greece and the islands, and the most useful. |

A general of the Warring States period (475 –

421

B.C.) with the symbol of the Olympic

games. |

|

|

|

BULCAN – BALCAN and XILLA ( Ellas), SILLA ( Silla), and SILA ( Sila) |

|

|

The southernmost province of China , Yunnan (in Arabic and Turkish Yunan ), is probably the cradle of the Ionian Greeks (Iwne s ). |

In northern Inner Mongolia an entire province and its capital are named after the sacred mountain Bulcan. From here Ghenghis Khan began his long march. |

|

The Turks whodescended from Mongolia gave the name of the sacred mountain Bulcan to their new home, the mountain range Aimos (Balcan). Today the term Balcania refers to Rumania , Serbia , Bulgaria , Albania, and Greece . |

In the 1st c B.C ., one of the three kingdoms in Korea and its territory were called Silla . |

|

In southern Italy ( Calabria ) a mountain plateau with Greek-speaking villages and olive trees in its southern region is called Sila . |

|

Coronation and decoration with band-snakes and belt-snakes |

|

|

Shiva winds a snake around the head of the victorious King Kola. From Temple Gangaikondalapuram, India,11th c. In situ. |

2nd c. B.C. clay Aphrodite. Snakes around the arm and ankle, and on the left thigh. Museum of Canakkale, Turkey |

|

Gorgo on an Archaic pediment with snakes around her waist. Corfu Archaeological Museum |

|

|

“Mother and child” Detail of a clay statuette (200 B.C. – 200 A.D.) Mexico City Museum of Anthropology and History |

Clay figure

from Vera

Cruz (900

A.D.)

|

The band of the victor on the forehead and around the arm |

|

|

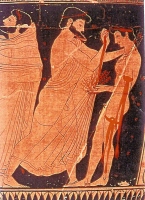

Crowning of a

victor in

Olympia

with

a red

band.

He already has bands around

the arm and

thigh.

Detail of a red-figured hydria found in an

Etruscan tomb in

Vulci,

Italy.

|

Red-figured

hydria (Nr. 2420) |

|

Steatite head of the King-priest from Mohenjo-daro (3rd millenium B.C.) The most important finding of the Hindu Valley , and Pakistan ’s national treasure. Band on the forehead and around the arm. I had already seen the photo many times, but all of a sudden noticed his armband. His right arm is missing, yet apparently both arms were decorated with ribbons, as in the photo of the Dragon dance. (On vases, usually, only one side is shown). |

|

|

The Charioteer of Delphi (470 B.C.). On the victor's band is the meander design, one of the symbolic representations of the snake. |

During the 2002 celebration of the Union with China in Macao, the heroes of the Dragon dance had red bands on the forehead and around the arm. |

|

Shaka, King of the Zulus, with the victor’s band on his forehead. |

|

JOHN AYTO DICTIONARY OF

|

|

|

Questions? E-mail Matt |

|

|

Help Support Matt's Greece Travel Guides |

|

Mount Olympus is

called

Mount Olympus is

called