A Short History of the Jews of Greece

Athens During the Occupation

Athens, however, was different. Neither the German nor the Jewish authorities

could obtain accurate information about the number of Jews in the capital. The Jewish population in Athens had

increased rapidly since the outbreak of the war. Few of these new arrivals were registered in the Jewish

community and most of them had no declared fixed place of residence. German intelligence about the Jews of Athens

was limited and often wrong.

Athens, however, was different. Neither the German nor the Jewish authorities

could obtain accurate information about the number of Jews in the capital. The Jewish population in Athens had

increased rapidly since the outbreak of the war. Few of these new arrivals were registered in the Jewish

community and most of them had no declared fixed place of residence. German intelligence about the Jews of Athens

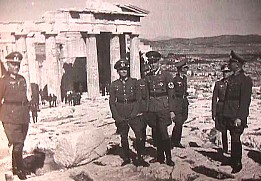

was limited and often wrong. On 20 September 1943, the Rosenberg Commando, still headed by Dieter Wisliceny and fresh from its successful operations in Thessaloniki, arrived in Athens. The German military commander in Athens wasthe newly arrived SS General Jurgen Stroop, whose success in liquidating the Warsaw Ghetto in May, 1943 had given him a reputation for ruthless efficiency.

Within 24 hours of arriving in Athens, Wisliceny ordered Chief Rabbi Elias Barzilai to appear before him. Wisliceny wished to obtain precise figures about the Jewish population in Athens and to create a Judernat. The Judernat had been a successful means of dealing with most of the Jewish communities in Europe. In essence, it usually consisted of a newly appointed president assisted by a new community council, generally made up of the more docile and coercible Jews. Assisted in many instances by a Jewish ‘police force,’ it was responsible for maintaining law and order and for acting as a liaison between the German authorities and the Jewish community. Neither of Wisliceny’s wishes were fulfilled in the next few months.

Barzilai had taken the precaution of informing the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church, Archbishop Damaskinos, of his summons to Wisliceny. He had also sent notice to the leading members of the community. With some of the members of the community waiting outside, Barzilai met with Wisliceny and was ordered to provide the following information:

1. The names, including addresses and professions, of all the members of the Jewish community in Athens.

2. The names of all foreign Jews, with details regarding their origin and nationality.

3. The names and addresses of all Italian Jews, including all Jews who had obtained papers through Italian assistance, living in the city.

4. The names of all Thessaloniki Jews residing in Athens.

5. The names of all people who had assisted Jews with ‘foreign’ nationality to escape to Palestine.

6. The names of the members of a new council to be formed under Barzilai’s presidency. The first act of this council was to create a Jewish police force for carrying out the Nazi demands. They were also to create new identity cards for all of the Jews of Athens.

Barzilai left Wisliceny’s office in a state of great anxiety and fear. In the course of the day appeals were made

to Greek authorities, but most of them fell on dear ears. Archbishop Damaskinos had perhaps the most logical answer

of all. A man of great courage and compassion. Damaskinos knew very well what had taken place in the north. His

advice was simply that the Jewish community should dissolve itself and take flight as best it could, for there

was not way it could be protected adequately. An appeal was made by a group of Jews to prime minister Constantine

Rallis on 22 September. Rallis tried to alleviate their fears by saying that the Jews of Thessaloniki had been

guilty of subversive activities. He also implied that they had been a foreign element in Greek life, which was

not the case with the Jews of Old Greece (those parts of Greece liberated by the Greek War of Independence in 1821).

In a sense, what Rallis said was that the Jews of the north had got what they deserved.

Barzilai’s problem was made more acute by the absence of the community records, which had disappeared under

mysterious circumstances some time earlier when the community offices had been broken into and robbed. The belief

at the time was that they had been taken by E.S.P.O., the fascist Greek organization. An exceedingly uncomfortable

Barzilai reported to Wisliceny the following day, adding that it would take time to draw up a new list of community

members. In fact, the community records had been destroyed by a group of Athenian Jews who feared their falling

into Nazi hands.

Barzilai was little prepared by temperament or experience for the heavy responsibility placed upon his shoulders.

Koretz’s role in assuaging Jewish fears in Thessaloniki before the deportations was fairly well known, and many

Jews in Athens, particularly whose who had escaped from Thessaloniki, became convinced that Barzilai must be sent

away. On 25 September Barzilai was shaved, given a new identity card, and sent off to the partisans in the mountains,

thereby thwarting the Nazi’s initial attempt. There was neither a list of community members nor a Judenrat.

True to form in choosing important Jewish holidays for some of their more monstrous acts, the Germans issued

a new order on the eve of Yom Kippur, 8 October 1943. This order, signed by General Stroop, was designed to organize

the Jewish community under direct Nazi supervision. Jews were ordered to return immediately to their place of residence

as given before June, 1943. They were to appear within five days at the community offices to declare this residence

and register their names. A new community council was formed with Elias Hadjopoulos as rabbi, Moise Sciaki as president,

and Isaac Kabili as vice-president. Despite the order, only 200 people had registered at the community offices

by the end of October. Considering that the Nazis apparently thought there were at least 6,000 Jews in Athens (there

probably were only 3,000), they were extremely patient.

Despite these possibilities of escape, more and more Jews gradually registered throughout the winter months. Many did so because they could not work without being registered, and many did so for fear of reprisals that might be exacted on Christian neighbors who were hiding them. By early March, 1944, approximately 1,500 Jews had come out of hiding and enrolled on the new community register.

From October 1943 to March 1944 the Nazis were busy compiling their intelligence reports on Jews elsewhere in Greece and preparing their final ‘action.’ Passsover that year was to occur on 8 April, and in early March a new bait was extended to the Jews of Athens. It was announced that special flour was to be brought to Athens for preparing matsoth. At a time when ordinary flour was a luxury, it is difficult to comprehend how this ruse could have tempted anyone who had kept hidden for several months. This apparent act of kindness, however, broke the nerve of quite a number of Jews, somewhat in the same manner as a small act of kindness given a man under torture can completely throw him off guard.